In the media, Kolobezkovyportal

Interview - Pamir crossing in winter

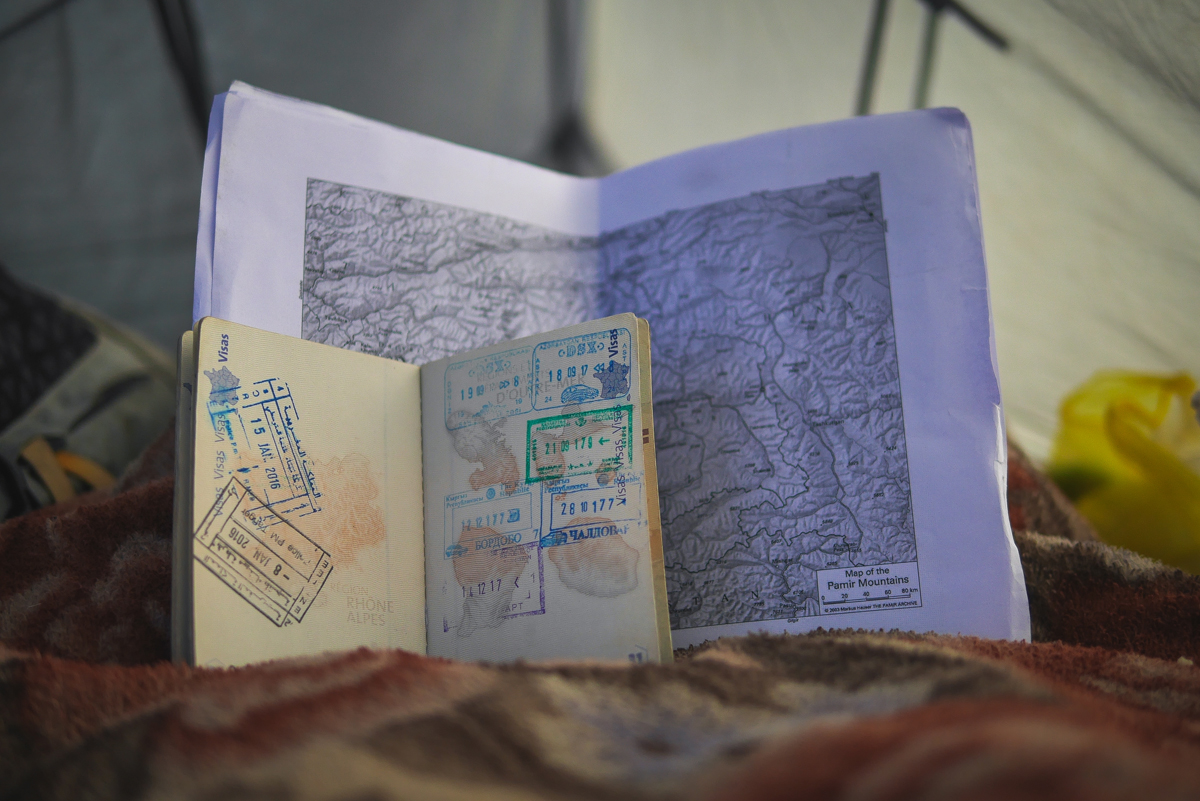

The following interview, dating from January 2018, was translated to Czech by Jan, and is posted on Kolobezkovyportal.

So you decided to go through Pamir in winter time? Why? And how was it?

Yes! After kicking through Kazakhstan (because the country is huge and I had only 30 days allowed as a tourist, I also took a train: great experience to hop on the local slow machine that crosses the barren lands of the steppes, for my part a 20 hours ride during which I had plenty of time to enjoy tea and share food with families, play with children, see old men sleeping 10 hours in a row, deal with hostiles or friendly wagon chiefs, find a place for the bike…), I reached Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan. The Pamir Highway (most of it is in Tajikistan), the second highest highway in the world (after the Karakorum Highway linking China and Pakistan) and only continuous road through the Pamir mountains, had always been on my mind. Because of its history, location, toughness, dangers and delights, it has become a kind of graal for two-wheeled and Jeep travelers. I was around quite late, if one consider summer or autumn to be the best time to get through it. But, on the other hand, could I really skip it just because people sitting on their couch would think it’s ill-advised to get their in winter? I realized I would probably not be where I was in the first place if I’d thought like that each time something was not « advised » by the doxa. And I was really attracted to experience winter conditions and add a few skills on my adventurer’s list. Moreover, after some researches, I knew that it was perhaps more secure to kick it in mid-winter than in early spring (would have I waited for it), because of the frequent avalanches and land sliding that happens when the snow melts. I knew also the cold would be a dry cold up there (which is better than wet conditions), and that big snow falls generally started in January. So I made up my mind rather confidently. Despite of what some people think (and I must say it is men most of the time), I’m very much aware of risks and situations whenever I decide to go there or there. Only, it’s not because risk exists that one does not have to deal with it. That’s the core of adventure. On top of that, improvising along the way does not mean that one is not prepared, on the contrary, « improvising with rationality » is, in my opinion, the sign of a seasoned adventurer, but not everyone can catch that spirit, or want to live with it.

Anything that surprised you in terms of surviving Pamir by scooter?

I knew it would be tough. Getting there in summer on a bicycle is already hard enough, at least for the high-plateau area, which constitutes the oriental part of Tajikistan. But I had considered that kicking through Kyrgyzstan in the first place (a country which is as well mostly mountainous) to reach the doors of the Pamir would prepare me and give the first lessons of living outdoors in a serious coldness. It was the case.

I was getting there from Osh, so it also meant the ascent to reach the plateau was much stiffer than coming from Dushanbe. And lastly, my equipment was not really at the level of the conditions I’d have to face : my sleeping bag, after 2 years of intensive use is weary and showed its limits at -15°C, I could not get winter tires in time, and I had few solutions to keep water from freezing, etc. On the other hands, I knew a bunch of survival tricks that could help, and had anticipated some of the conditions from the very beginning of my life on the road (small pikes for the shoes, DIY vapor barriers, etc). But this is a delicate matter which deserves a dissertation on its own: to affront extreme conditions, or even in average ones, does really one have to get top-notch modern gear that states on the paper that this or that can be done with it ? I believe here again it’s mostly a matter of common beliefs and modern doxa ; how about pushing what you actually have at hands to its limits ; and what about traditional ways of dealing with cold, etc ; why not mix technics ; why not continue to be inventive on the way, etc. Is your journey about travelling in comfort with no survival issues (in which case people often take planes to get in other parts of the world when cold comes, etc), or is it about something else ? Each traveller has his own reasons for travelling, and does it in his own way. My way is not only an exploration of the world, but an exploration of the proper or « fair means » one can use to explore the world nowadays. In short, the lesson of a contemporary journey concerning technics and gear fits in an anecdote: when you think you will observe how locals Kyrgyz deal with the cold and you wish to adopt their manners, waiting for fur and leather mitts made of their own animals, you will mostly find that they wear industrial cotton and rubber gloves… So there you are, as a 21st century wanderer, you have to invent your own traditions on the go.

Back to the Pamir crossing. I got dehydrated pretty fast, I hardly slept at nights, I got sick, I walked most of the time on snow and ice, climbing slowly from Osh to Kara-kul, in colder and colder weather. Before one enters Tajikistan, one first has to reach Sary-Tash, a small village facing the nothern trans-Alai range of the Pamir. I arrived there already washed out by the ascent from the low lands. I was already suffering from cold at nights, and beginning to feel how altitude was impacting my performance. I took a few days to rest there in a guesthouse and decide whether or not I should try to get further in the barren high-plateau of the Pamir, which I knew would be a challenge to reach. Because I had no mean of getting a warmer sleeping bag quickly, I decided to give it a try, see how far I could push the gear and myself. It was now or never, as, as the days passed by, it would be colder and colder, and I knew big snow falls were generally expected at the end of December. I could always turn back to Sary-Tash if it became impossible or life threatening.

Well, the first night after I’d quit this little village, I had probably the worst night I ever had in the entire journey. It was -20°c, windy, and I was ill all night. Not only was I suffering from cold in the sleeping bag, but I had to rush out every hour in the snow and subzero temperatures… Next morning, I was headed forward, already deprived of sleep, dehydrated, and not very well. I had the next pass in mind. I was thinking if I could reach this one and get into Tajikistan, I’d have reached the plateau, and it would be easier. So I kept on walking and pushing. It took me one day and a half more to reach the summit and pass. And had I not been welcomed by a family in a very improbable house in the middle of nowhere, I’m not sure I’d have continued. This was an intense moment, and I will never forget the evening, night and morning I spent amongst them, sharing meal, smiles and a roof. There was a 4 months old baby, and it was fascinating to see how babies are taken care of here, in beautiful painted wood curbs, covered with thick fabrics so that the baby is in the dark, just like a bird ! It was also wrapped up pretty tight in the sheets.

At the Tajik frontier post, the guards were really friendly and bewildered by my sleeping outside in this time of year. They were happy to provide half a blanket when I ask them. It did not suffice though to insulate much more from the cold. Night temperatures were dropping to -30°, and, when you are not used to it, it’s a strange feeling to let oneself go into an obscurity pondered by extreme coldness. You can feel everything turns immobilized and frozen, like seized by an invisible but powerful claw, just like when you picture a water flow turning to ice in an instant, or lava turning to rocks… Then one only has to let oneself slip into that frozen darkness, and feel in the deepest part of one’s being, the function and power of one’s energy as it gets spent in warmth and lost so quickly. One comes to cherish the smallest intake of energy and weigh, in each action, whether there will be too much energy lost or whether it is worth it (as in melting some snow in the winds, etc).

A dog appeared at some point, from nowhere it seemed. We had a strange cohabitation, him and I. He never agreed to come into the tent and sleep on my feet, which could have been such an amelioration of the nights for me and for him as well, I thought! But he kept on following me for 2 days, getting synchronized to my rhythm, as I sometimes was taking pause every 10 steps or so to breathe again (I told the story about the dog here: https://www.facebook.com/latrottineuse/posts/1645560195490064)

Overall, some days I have walked only 12 km of stiff ascents. Mentally it was super hard. Physically I was loosing stamina and deteriorating at a quick pace. At a point, I had decided to abandon. I had just passed Kara-kul, and the highest pass was still to come, but I knew continuing on that road would mean a good deal of days and nights without a single village or home to rely on. I estimated I would not have the strength and enough supplies to do that, as I was already pretty tired from getting here from Osh. It was the first time I renounced before an obstacle. It was terrible, psychically, but reason was talking. I then had the toughest time to get back to the village of Kara-kul, 20km before, after a dreadful morning (I’d slept under the road in a small round tunnel, and wind had become pitiless during the night). I could only reach the door of the first Gastinista (homestay/guesthouse) I spotted, near to fainting. I recovered quickly, « chai » does marvels around here. And heat of the stove too. But, each time I was thinking of stopping the trip, (it happened a lot during those weeks) something significant happened. I’d encounter a place or someone that would allow me to gain back some energy, the smallest thing would work. And then my body would just continue, going forward, going further ahead, see where I could get. That’s how I got back on the board, in Murghab (which I reached in a pick-up to pass the Ak-Baital pass), and so on, switching between hitchhikes and kicking until Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan. Getting lower again in altitudes meant conditions were easier, and I could kick along Afghanistan without much trouble, though it was very slow again to progress on ice, and then rocks.

Overall, I consider my Pamir crossing as a semi-failure. I’m not happy that I could not entirely make it through on my own. But I’m not so unhappy that walked up there, « survived » -30°c nights and harsh conditions only with what I had, after nearly 2 years of continuous travel on the push scooter. And with the extremely precious help of people, from time to time, that I will never forget. When I think of it, I would do it again in the same conditions, for I have seen the most surreal places, that only a winter time offers to the eyes, senses and mind, just as if I had landed on another planet, in another galaxy.

Why have you returned back to Osh?

Because I had to kick the M41 (Pamir Highway) coming from Osh (in the north), I went somehow backward towards the west. Coming back to Osh is looping the loop and getting ready for what will be next.

And nearest plans? China or India? Why?

Ha ! I think I feel I owe the journey another shot at doing something a bit crazy. I gained experience and took stock of the Pamir crossing. There is a mythical knot (not only the Pamir mountains as the center of mythical mountain ranges as the Hindu-Kush, the Tien-Shan and the Himalayas) just East of here… It’s the place where different segments of the Silk Routes would rejoined, before or after (depending if you were coming from the east or west) the Taklamakan desert (in west China, Uighur autonomous regions). From there, one can go south or north of the desert, and go on towards the Indian subcontinent, or further inside China. The Taklamakan is known as the « Sea of death », « the Place of no return », and has drawn as much explorers and merchants through its moving dunes, that it has kept animals and humans to the end of times. Nowadays, people travel along it on its north or south limits. I want to cross it right in the middle, and in winter again! There are new roads built by China for industrial purposes (as often with new roads), which stretch for hundreds of kilometers without anything else in sight than dunes and asphalt. If I get the Chinese visa (which is nearly impossible when you are a foreigner in Central Asia, so I have to arrange through a French agency), and succeed in that epic desert crossing, then I want to kick to the highest highway in the world, which is the Karakorum highway (KKH) that gets through Pakistan into India. This is the plan today, anyway.

Thanks Jan 🙂